Erectile dysfunction is a stumbling block for all couples in the world. It troubles partners unexpectedly and ruins their relations. Men become silent and try to avoid spending time in their women’s company. Women start thinking that something is wrong with their appearance and that men cannot erect because they are not attractive anymore. Cialis is a drug that can make men’s intimate relations not so complicated. Tadalafil brings back erection back to the norm and women start feeling pretty and desired again.

Cialis Can Be Different

It’s a well-known fact that there are two types of drugs according to their origin: brand and generic ones. Many people think that they differ much. They think that only brand-name medicines can produce the best effect and cope with the problem. The truth is that generics are mere analogs. They have the same composition and can treat the same health disorders.

So, what’s the difference? Why does this distinctive feature make people think that brand-name drugs are better than generics? The matter is in their price. Generics are cheaper but a cheap thing doesn’t always mean a bad thing. The research shows that contemporary pharmaceutical companies spend huge sums on research to have the right to sell solid drugs with an excellent reputation. Generics take the formula and rename the medicine. They economize on international fame but reserve the quality. So, there is no need to pay more to get the desired results.

Generic variants of Tadalafil are also of high-quality. They differ in strength, shape, and form. There are six main analogs of Cialis.

Cialis Soft Tabs

These tablets have a strong effect and improve men’s health. Erectile dysfunction is a delicate problem and it requires a soft solution. Cialis Soft Tabs produce such an effect and help to gain a natural erection.

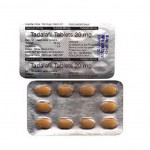

Generic Cialis

The generic variant of the brand doesn’t differ from the original. Its price is lower and when buying a blister that contains more than 100 pills, a person can save a solid sum.

Female Cialis

This is the only drug variant that can be taken by females. Scientists have found out that women can also lack sexual desire after menopause, childbirth, and surgery. Female Cialis brings back sensitivity of the clitoris. It leads to better lubrication and a woman feels pleasure instead of irritation and burning provoked by the dryness.

Cialis Black 800

Cialis Black 800 is not to be taken by males who have first signs of impotence. Only patients who have serious problems with erection and even neglected impotence take Black Cialis. Doctors prescribe these pills to those who also lack libido and stamina. One pill contains 80mg of the active component. It means that they are strong but can cause severe adverse effects in case of improper intake.

Cialis Professional

Men with impotence need professional help. Cialis Professional has an improved formula. Their aim is to find the reason, delete it and let a person experience a stable erection that promises satisfaction in bed for both partners.

Cialis Super Active+

If a person needs to raise the level of testosterone, improve erection, get rid of premature ejaculation, and experience sexual arousal, then it’s high time to take Cialis Super Active+. Compared to other generic variants, this type starts working in 5-7 minutes. That’s their PLUS.

Where to Get Pills?

Online pharmacies can supply people with the generic every man needs. The online drugstore offers high-quality products, discounts, and bonuses for regular customers and quick service to let everyone get the drugs as soon as possible.

List of verified online pharmacies:

- canadapharmacy.com

- canadadrugsdirect.com

- northwestpharmacy.com

- costco.com

- cvs.pharmacy

- pillpack.com